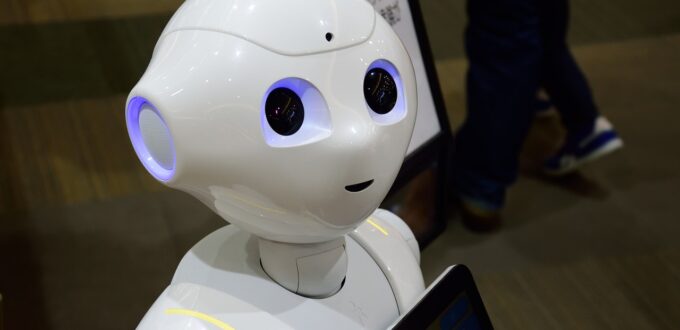

Meet Nao. Standing at 58cm tall, he can speak 20 different languages, recognise faces and detect obstacles.

The programmable humanoid robot’s newest venture will play a key part in a South Australian-driven research project investigating how robots can help care for the sick and elderly.

Project Heart is expected to unfold in Renmark in South Australia’s Riverland to study brain activity in patients and elderly people when they interact with a robot compared to a trusted human carer.

Prominent thought leader, cognitive neuroscientist, founder and CEO of the NeuroTech Institute, Dr Fiona Kerr, is leading the research project alongside Flinders University and French humanoid robot designer and manufacturer Softbank Robotics.

Expected to kick off later this year, Project Heart will explore human-to-human interaction versus human-to-technology interaction and how robots can be effective in helping the elderly remain independent.

Dr Kerr has centred much of her works and research around exploring the impacts of artificial intelligence (AI), human connectivity and technologisation and always asking the questions we often overlook.

“One of the things we really need to understand when we use robotics for care is what is missing? What are we not thinking about?” she says.

“We know that certain parts of the brain don’t stand up when looking at someone over a screen for example compared to looking at someone (in the flesh) one on one. We have all sorts of chemicals and synchronisation happening right now because we are in the same space, we have a bunch of endorphins, oxytocin and dopamine release.

“Lots of things happen when we’re in the same physical space as another human being. But when we have technology, what turns on and what doesn’t?”

The first phase of Project Heart will have patients interact with Nao while wearing an EEG (electroencephalogram) head cap to record brain activity.

“We watch what happens when Nao comes in to see a person and what their brain does, what socio and emotional parts of the brain turn on and what parts don’t. I will be recording the data, then a trust carer they know – the human – comes in and we see the difference in what happens with the brain.”

The second phase of Project Heart involves Nao living with a senior person in their home, and the participant being monitored regularly to “see what changes in their brain over time”.

“Nao can chat to you, play games, get you to move, remind you what to eat, connect you to your daughter or son, carer or doctor, make appointments, ring taxis, all sorts of things,” Dr Kerr says.

“Because it’s watching you, you don’t need a sensor if you fall over. Nao will see you and immediately tell someone, and if you’re not moving it will just call an ambulance. But is it an alternative to human company? No way.”

Dr Kerr, Brand South Australia’s latest I Choose SA ambassador, has spent more than 30 years gaining knowledge and qualifications in cognitive neuroscience, complex systems engineering and anthropology, and maintains that no matter how great the advancements in technology, sometimes there is no greater substitute for the human brain.

“AI is as dumb as slime,” she explains. “We love it and it’s very fast at certain things because it’s a pattern generator, but it has no capacity for abstraction or empathy. We go quantum, they don’t. If we have a complex problem, then we are abstracting and some of our brain is working at quantum speed, it’s just incredible what we can do. AI can do none of that.”

Dr Kerr also dedicates her time as a research fellow at SAHMRI and works in her capacity as a neural and systems complexity specialist at the University of Adelaide. Other NeuroTech Institute projects include working with companies such as Cirque du Soleil and US Defence, to explore how soldiers interact with autonomous systems, and helping Finland design its AI program.

Advising Finland’s AI steering committee, it’s Dr Kerr’s job to ask questions like ‘what do we know about AI?’, ‘what don’t we know?’, and ‘what questions should we be asking that we’re not?’

She says there are two approaches to AI and automation, a quality relationship with technology and a quantity relationship with technology. An example of the quantity approach would be cutting jobs and introducing automation to increase profit – which Dr Kerr says is often only a short-term result.

“You actually hook yourself to the dumbest AI, the dumbest progress in technology, whereas if you choose the quality road then what you’re saying is we want to know how cutting-edge technology augments human capability,” she says.

Examples of AI, automation and machine learning are already unfolding – and have been for decades. The iPhone is an every day example, while many cities have welcomed smart paths, smart lighting and smart infrastructure, while our skies host drones used in agriculture, defence and mining.

But some countries are moving faster than others. Take Sweden, where thousands of people have chosen to insert a small microchip the size of a grain of rice under the skin between their thumb and index finger allowing them to unlock their homes, turn lights on and off and buy groceries with a swipe of a hand.

Dr Kerr says the key to success and balance with AI and automation is to ensure rule bearers and policy makers put regulations firmly in place to ensure ethical matters are addressed.

“Human beings in general love to technologise, we love the bright and shiny,” she says. “I love technology, but we need to make sure that it’s enabling us rather than ruling us. It’s that difference.”

Source: Brand South Australia News